Iqaluit

STATISTICS

Estimated Cost: $750 M

Target Construction Start: October 2028

Target First Power: December 2030

Proposed Energy Supply: Waterpower

Population

Peak Electricity Demand

Proposed Source

Diesel Offset

Statistics

Estimated Cost: $750 M

Target Construction Start: October 2028

Target First Power: December 2030

Proposed Energy Supply: Waterpower

Population: 7,430

Peak Electricity Demand: 10,300 kW

Proposed Source: 15-30 MW

Diesel Offset: 100%

Project Story

The Iqaluit Nukkiksautiit Project could revolutionize Nunavut’s energy supply as the territory’s first-ever water-powered electricity project. It aims to completely replace diesel as the city’s electricity source.

Iqaluit community members chose this project in 2023 through a ranked ballot vote after several years of research and discussion. The proposed concept would harness water power from the river at Kuugaaluk, about 60km Northeast of Iqaluit.

Early Efforts

More than 20 years ago, Qulliq Energy Corporation (QEC) began this project, with hopes of bringing water power to Iqaluit from the rivers at Qikirrijaarvik (Jaynes Inlet) and Nunngarut (Armshow River). Inuit did not want those rivers developed because they are so important for hunting, fishing, and camping. For that reason, and due to high cost estimates, QEC stopped development in 2014.

The Qikiqtani Inuit Association (QIA) took over the project in 2017, with interest in developing water power at Kangala (Ward Inlet) or other areas of Inuit Owned Land. They knew that transitioning away from diesel was very important to Inuit, but needed it to be done respectfully. They also knew that Nunavut Nukkiksautiit Corporation (NNC) was well suited to lead the project. In 2020, NNC took on that role, in collaboration with QIA.

The Options

NNC studied the information gathered by QEC and QIA. We wanted to know: Are we missing anything? And how do we make sure that cultural, technical, and environmental priorities are weighed equally? So, we hired scientists and engineers. We worked with QIA to conduct a Tusaqtavut study on Inuit land and resource use. We also toured the area around Iqaluit by helicopter, looking for places where wind, water (or a combination of the two) could bring clean power to the community. We didn’t consider nuclear power because that technology isn’t ready for such a small-scale setup. Solar was also ruled out because it’s mostly dark in Iqaluit all winter, and the number of solar panels needed to power the city would take up a very large area.

After many months of work, we found 16 different options within a 100km radius around Iqaluit. In 2023, NNC held a series of gatherings to share these options—the whole community was invited by postcard and special invitations were sent to Rightsholding organizations.

We explained the advantages and disadvantages of all options, including continuing with diesel. Then, we held a vote—all who came to the gatherings could cast a ballot, ranking their top 3 choices for clean energy. Of the people who voted, 76% agreed that water power on the river at Kuugaaluk was the best choice. This place showed the lowest amount of Inuit land use, based on the Tusaqtavut Study’s interviews with Elders and hunters.

Studying Kuugaaluk

Since then, NNC has received federal funding to study this option. We have worked with the Hunters and Trappers Organizations in Iqaluit and Panniqtuuq to make study plans for the land, rocks, water, plants, animals, and Inuit artefacts at Kuugaaluk. These studies began in 2025, with 70% Inuit employment on site. There is a lot more work to be done. NNC continues to prioritize Rightsholder engagement with Iqalungmiut and Panniqtuumiut, and working together to define and seek free, prior, informed consent for the development of this project. If it moves forward, the project could reduce Nunavut’s diesel use for electricity generation by one third.

Impacts & Benefits

One of the most important tasks in developing any project is understanding what its possible impacts could be. That is, if the project were built, would there be any changes to the land, water, air, plants, animals, and the ways in which Inuit exercise their Rights under the Nunavut Agreement?

Full Story

In order to understand potential changes, we must:

- Work together with the Amaruq and Panniqtuuq Hunters and Trappers Associations to make study plans

- Send teams of scientists and Inuit guides to the site

- Collect and analyze data

- Share everything with the public

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit must be integrated into the study findings, by Inuit, to make sure that data get interpreted in a way that makes sense with what Inuit know to be true. We have to do this for at least two years, to know how things are now, before any construction is considered.

With the help of technology, we can make models of the environment at Kuugaaluk and see what happens if a water power plant was built on the river. That is how we can predict possible impacts. It’s not possible to know until all this work has been done.

Sometimes, as was seen with the Innavik Project in Inukjuak, a water power plant can actually improve animal habitats by making water flows more consistent and increasing oxygen in the water. It’s possible that fish populations could increase.

However, if the models show that the project would impact how Inuit enjoy the land, harvest, and exercise their Rights, we must find ways to minimize those impacts.

Furthermore, the Nunavut Agreement says that if a project causes any changes to how Inuit use the land—even positive changes—Iqalungmiut and Panniqtuumiut will receive benefits.

These benefits can take the form of money, infrastructure, cultural programming, training and employment, or any other investments that match community priorities. Legally, the Nunavut Agreement requires us to negotiate benefits agreements with the Designated Inuit Organization—QIA. NNC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Qikiqtaaluk Corporation, which in turn is wholly-owned by the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, making this a unique situation. We can also look beyond a traditional Inuit Impacts and Benefits Agreement structure to best meet the needs of communities.

As of 2025, conversations have started with QIA on how benefits agreements can take shape, and the ways we can collaborate directly with Iqalungmiut and Panniqtuumiut through this process. The only way this project moves forward is through respecting the Nunavut Agreement, territorial regulatory systems like the Nunavut Impact Review Board (NIRB), and the voices of Inuit. We look forward to keeping communities informed on the project’s potential impacts and benefits.

Overview Community Engagement

NNC has been engaging the community since the very beginning, but in 2024, this strategy was approved by QIA. It moves with the seasons of Inuit culture. There are five main goals throughout the year, and the cycle begins again each year until the project stops or is completed. Since Kuugaaluk is an area that Iqalungmiut and Panniqtuumiut are connected to, all engagement as of 2025 includes both communities.

It all starts in the early spring—NNC meets in-person with the Amaruq and Panniqtuuq Hunters and Trappers Associations (HTAs) to plan the summer field season at Kuugaaluk. Right now, that means co-developing study plans for collecting data.

In the spring, we share the field season plan with the public, and begin hiring local Inuit who are interested in going to Kuugaaluk to support the studies.

Updates are shared from Kuugaaluk throughout the summer field season on NNC’s social media page, in weekly emails to the HTAs, and in a public quarterly newsletter.

In the fall, it’s time to host public events in Iqaluit and Panniqtuuq, where all the results of the summer field season’s work are shared. We’ll analyze data together, and make sense of it using Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and western science.

Finally, in the winter, we’ll host more public events focused on education and/or consent-seeking. There’s a lot to learn about water power, how it has worked in other parts of Inuit Nunangat, and the project’s development progress. We want to hear from Iqalungmiut and Panniqtuumiut on what they’re curious about, what they like, and what they’re concerned about. If we’re at a decision gate (a point in time when we need Rightsholders’ approval to move forward on development), we will look to the community for direction.

This engagement strategy keeps community members and Rightsholders up to date every step of the way. When more discussion or changes are needed, we hold additional events and sessions, making sure everyone has an opportunity to have their voices heard. Anyone can reach out to NNC at any time to ask questions, make suggestions, or share feedback.

We love to hear from you!

Timeline

IAC Inuit Advisory Committee

This group of nine Inuit from Iqaluit and Panniqtuuq work together to guide engagement and consent-seeking methods, and increase Inuit perspectives on the project as a whole. Although this project is aiming to provide water power to Iqaluit, we want representation from Panniqtuuq as well, since they are also connected to the land and river at Kuugaaluk.

From Iqaluit, there are two youth, two elders, two at-large reps, and a board member of the Amaruq HTA. From Panniqtuuq, there is a board member from the HTA, and one at-large rep. The Inuit Advisory Committee meets at least four times a year to help prepare for engagement events and review lessons learned. All members are compensated for their time at a rate of $250 per meeting, with additional honoraria for time spent on emails, any media communications, and an annual completion bonus. To keep the process fair, members are selected by a third party and may renew their positions each year for a maximum of three years.

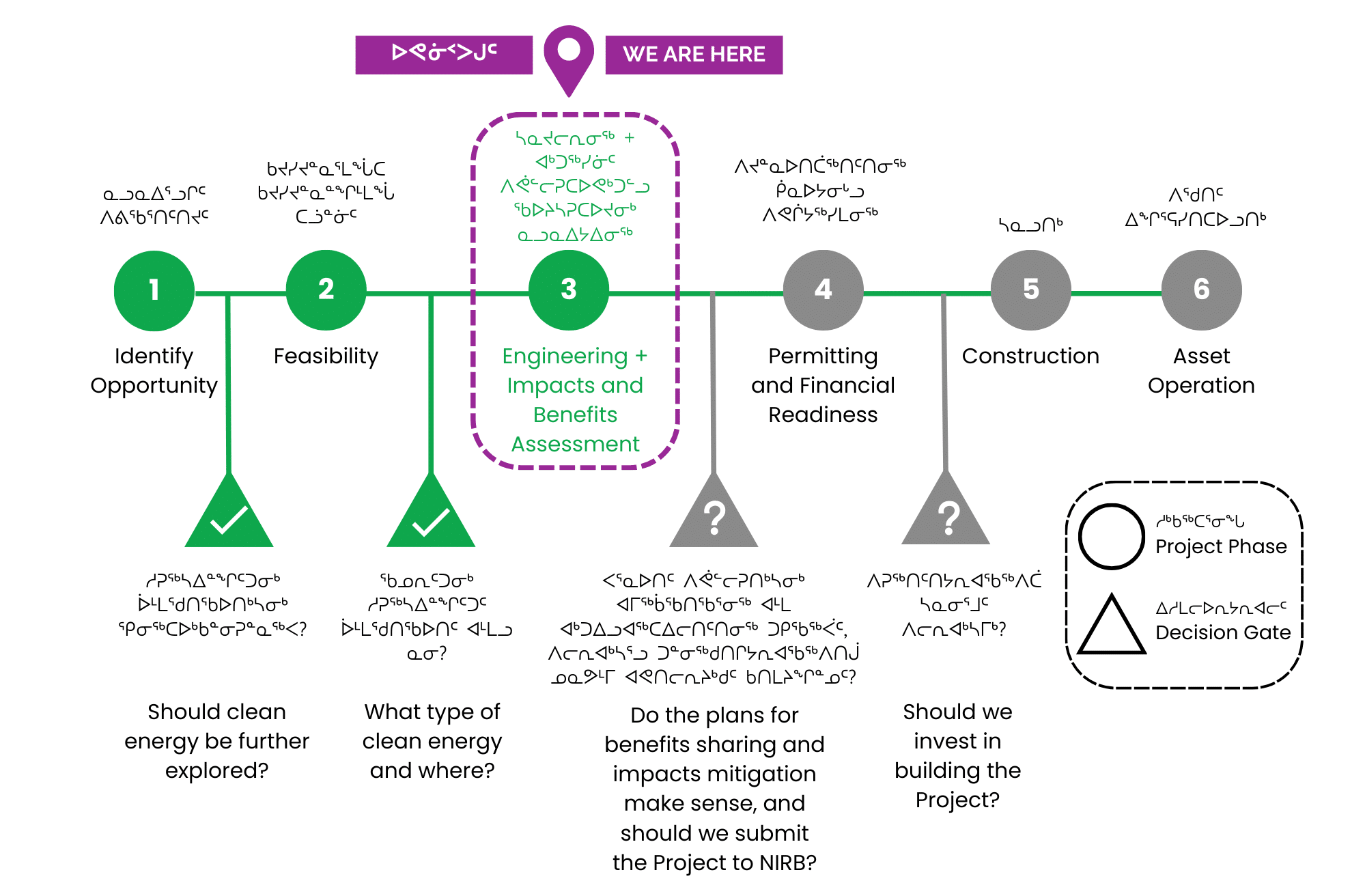

Phase Gate Development Process

This diagram shows how the project gets developed from start to finish. It’s called a phase-gate process because it breaks up the work into six phases with a decision gate in between each phase. A phase is a body of work, defined by a particular goal. A decision gate is a time when we look to Inuit leadership and the public for their consent on moving forward. NNC follows this process for every community project, and is always looking for ways that it can be improved.

NNC works with the project team to complete a phase. Then, we show that work to the community. To move through the decision-gate and on to the next phase, we have to find out whether or not Inuit are comfortable with progress and want us to proceed. There are three possible responses we could receive from Inuit at a decision-gate:

- no, we don’t want this — stop work.

- we want you to keep going, but we’re not happy with this outcome — try again.

- yes, we like this — continue.

Our goal is to find ways of building consensus, according to Inuit Societal Values. This means making room for all perspectives, finding ways to adapt plans, and addressing concerns. It’s very normal and okay for people to disagree. What matters is that we listen (to understand), provide transparent information, answer questions, be honest when we don’t know something, and make a plan to follow-up. Through this kind of dialogue, it is often possible to find respectful solutions and a path forward.

Even then, it’s unlikely that everyone will agree. What we look for is a strong majority of Inuit agreeing on one answer—we take this public feedback and present it to Inuit leadership at Qikiqtaaluk Corporation, and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, to assist them in their final decision.

Breaking the process down into manageable steps like this gives Inuit multiple opportunities to decide whether or not investment and work should continue in the way that it’s being proposed. If this project gets built, it’s because Inuit say “yes” four times, all along the way. This is the backbone of how we apply the concept of free, prior, informed consent to the clean energy transition in the Qikiqtani region.

1. Identify Opportunity

First, we figure out if it’s possible to develop a renewable energy source for the community. This means taking a look at existing data we have access to from the government, Inuit Organizations, and other groups involved in understanding local natural resources.

This usually takes a few months.

Decision Gate

From this early study work, we create a Decision Support Package for Inuit leadership.

The Presidents of Qikiqtaaluk Corporation and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association use this to answer the question: Should NNC go forward on finding all the options for renewable energy development?

If yes, they return a signed copy with their authorization and direction to look into the opportunities more closely.

Resources

- Resource link 1

- Resource link 2

- Resource link 3

- Resource link 4

2. Feasibility

Next, we come up with as many options as possible, in terms of technology type and location. The land, water, wind, and sun around every community is unique.

We need to carefully consider how to maximize power and/or energy production from the renewable resources we have access to. In some cases, this could mean combining more than one source. Often, NNC will install a meteorological evaluation tower, with instruments at the top for measuring wind and sun.

This phase usually takes about a year.

Decision Gate

All options are presented to the public and Rightsholders for consideration. Every effort is made to communicate the important details, advantages, and disadvantages of all options in different ways: storytelling, presentations, one-on-one conversations, posters, booklets, and group question-and-answer sessions. Everyone who attends the engagement events votes for their top three options (all options are listed on the ballot, including the option to continue with diesel).

Participants can take their ranked ballots home and mail them in up to two weeks afterwards—it’s important to take time to digest and consider the information. From these ranked ballots, NNC looks for a strong majority in order to choose the favourite project option for development.

Resources

- Resource link 1

- Resource link 2

- Resource link 3

- Resource link 4

3. Engineering + Impacts & Benefits Assessment

Once an option is selected, the engineers can really get to work. This is also when we start collecting data from the chosen site for the project. Teams of Western scientists and Inuit knowledge holders make study plans together. They spend time at the site and learn together about the land, water, wind, sun, animals, plants, rocks, and Inuit artefacts from long ago. This feeds into design and engineering; which, in turn, allows us to create a business case for the project. NNC negotiates commercial contracts with QEC to decide how water power can be bought and sold, and connect into the existing grid for the community to use. We also do a socioeconomic study to see how the project would affect life in the community, the cost of living, opportunities for local businesses, and employment.

Everything is shared with the public, and interpreted through an Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit lens. Lots of discussions are held with Inuit connected to the site so we can understand their perspectives and needs. We ask Inuit: What benefits do you want and need to see? How would you like us to approach minimizing impacts? How can we make these plans better?

We ask Inuit:

- What benefits do you want and need to see?

- How would you like us to approach minimizing impacts?

- How can we make these plans better?

This phase takes 2 to 3 years.

Decision Gate

At this point, we have a strong understanding of what the project will look like, how it could be built, possible environmental impacts that could be expected, and strategies for minimizing them backed by Inuit knowledge. We also have a framework for an Impacts and Benefits Agreement with QIA and any additional plans to share benefits.

- Step 1: We present this to Inuit and ask: Do you agree with the final benefits-sharing commitments, and do they line up fairly with our plan to manage possible impacts from the project? If not, how can we make sure they do?

- Step 2: We ask the public and Rightsholders: Should we submit the Project to NIRB?

Resources

- Resource link 1

- Resource link 2

- Resource link 3

- Resource link 4

4. Permitting and Financial Readiness

By now, we have completed all preliminary work. We’ve received clear support from Inuit that, yes, we should share the project plan with NIRB for legal environmental assessment, and to request permission to build the project. Our goal is for the submission to reflect a project that was co-developed with Inuit, and represents what the majority of Inuit want. After submission, we’ll need to wait at least 12 months, sometimes longer, for NIRB to hold hearings, consider all the information, and make a decision.

While we wait, we keep collecting environmental data from the site in order to get an even better understanding of possible impacts, and we keep engaging with the public to educate and receive feedback. We also frame out a financial plan for building the project, so we’ll be ready, in the case that we get NIRB approval.

This involves talking with lenders, banks, the Government of Canada, and possible business partners who could put money in.

Decision Gate

If NIRB releases the project from environmental assessment, and (based on formal, legal hearings with Inuit) grants permission to move forward, we take that decision package to Inuit leadership.

We ask the presidents of QC and QIA: Should NNC invest in the construction of this project?

If yes, they return a signed copy with their authorization and direction to proceed.

Resources

- Resource link 1

- Resource link 2

- Resource link 3

- Resource link 4

5. Construction

It’s time to build the project!

This phase brings a lot of activity, and a lot of jobs for Inuit. A road must be built out to the site, along with a transmission line that will carry the renewable power to the QEC plant.

Lots of electrical work has to happen at the point of connection, so that the grid can safely receive the new power source. Housing must be found or built for all the workers, including the local Inuit workforce. It will take at least two years, but maybe more, depending on what kinds of challenges are faced along the way.

Resources

- Resource link 1

- Resource link 2

- Resource link 3

- Resource link 4

6. Asset Operation

After construction is completed, we’ll be ready to “flip the switch” and send renewable power to the community. This is the moment that everyone has waited for.

Power will be sold to QEC, and QEC will sell it to their customers, as they always have. Once up and running, the new infrastructure will need workers to keep everything running smoothly, fix problems when they arise, and take care of routine maintenance.